CME this week changed their minimum contribution to the default fund. My initial reaction was that this change was designed to encourage smaller firms to self-clear their IRS business. It got me investigating default funds and the entire financial safeguards at CME and LCH in more detail.

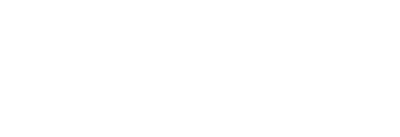

Default Waterfall

After reading through the CME rule book and the LCH Default Rules, one can quickly conclude that the financial safeguards of each clearing house is generally the same structure, as I have summarized below:

First off, a matter of terminology. CME and LCH use some unique terms when it relates to their default management process. For the purposes of what I write in this blog, I need to avoid this confusion so please use the following definitions:

- Initial Margin. Aka performance bond, and akin to maintenance margin.

- Default Fund. Amount of funds over and beyond the initial margin contributed by members. Aka “Guaranty Fund”.

- Clearing House contribution. What the clearing house would need to pony up at some point during a default. Aka “skin in the game”, “SITG”, Corporate contribution, Clearing house reserves.

- Unfunded Assessment. The potential liabilities that members may need to contribute to the default fund. Aka Assessment powers.

Stepping Through the Waterfall

Best to go through each point to understand them.

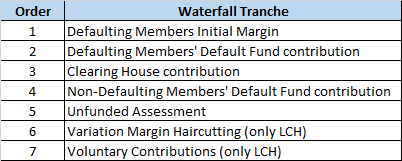

1 – Defaulting Members Initial Margin

Initial Margin is the collateral that backs up positions in swaps. Unlike standardized futures or traditional spot FX, even the most basic swap position is margined using a simulation, which finds some worst case scenarios for each swap portfolio based upon many years of historical 5-day market movements. We have blogged about this many times in the past and offer our CHARM tool to understand this amount.

2 – Defaulting Members Default Fund Contribution

Generally speaking, both CME and LCH calculate the default fund by performing a simulation on all accounts held. These simulations are “extreme but plausible” market movements. Think of these as what might happen if the Fed and other bodies cut interest rates 100 bp over a 5 day period, or a nation defaults on their debt causing a spike in yields.

By applying these scenarios to every account, the 2 worst performing accounts under the worst scenario are cherry-picked and summed up. Simply put, if the two largest losses total 3 billion dollars, the default fund is then sized at that amount.

EDIT: It has been clarified these two largest losses can come from separate scenarios, so the losses are “unsynchronized” with the scenarios. These losses are above and beyond the collateral pledged by each member (more than the initial margin pledged), hence the loss is a “potential residual loss”.

Then of course this 3 billion needs to be shared equitably (paid in equitably) among the members. CME is somewhat clear on how this is done:

- The majority (~90%) is based upon an average “potential residual loss” for each member over a trailing monthly period.

- The remainder (~10%) is based upon the gross notional position in swaps. This is presumably here to cater for the firms that are generally “flat” and hence low initial margin, but with many line items.

- The minimum amount, even for those with no positions, is the amount CME changed from 50 million to 15 million USD. At LCH this amount is 10 million pounds.

So that describes the size of the default fund and each members contribution to it. In this level of the waterfall, the defaulting members portion is utilized. We will see later how the surviving members portions are applied.

3 – Clearing House Contribution

Here, the clearing house themselves pony up some cash. This had become a hotly contested debate over recent years. The argument being that clearing houses are more of an industry utility. But because they are commercial enterprises, they need to have some of their own cash on the line to keep them honest, and practicing sound risk management. To do so, an amount of company capital has to be on the line in the case of a default – which is why you will hear the term “Skin in the Game”.

The other side of the argument is “hey, we (the clearing house) don’t bring risk into the system so why are we on the hook”. This sentiment doesn’t seem to gather much sympathy.

Anyway, the CME has been in that debate and recently upped this portion to 150 million dollars of its own funds. Interesting however that if I read it right, LCH’s amount is in the order of 35 million dollars.

4 – Non-Defaulting Members Default Fund Contribution

So if the clearing house’s own cash will not suffice, we will need to go further into the waterfall to cover the loss. Remember that 3 billion dollar default fund we looked at above? Let’s now look at how this is consumed.

First you need to understand that when a default happens for swaps, the clearing house cannot just “liquidate” the members’ positions. As was the case of Lehman’s default at LCH 15 years ago, there were 66,000 trades needing to be dealt with. So both CME and LCH (and other global CCP’s) have similar approaches:

- Bring Dealers from the Member firms into the Clearing house to hedge the position

- Auction off the Defaulting members portfolio. This can be done by currency, and in the case of LCH, sub-portfolios within currency, for example a short and longer dated portfolio. During the Auction, each member bids on each portfolio, and the winning bidder has the portfolio transferred to them in exchange for the funds

- At the end of the auction, some total default loss can be determined now that the proceeds have arrived.

So if the total loss is great enough that the non-defaulting members guaranty funds are used, it is applied as follows:

- Members that failed to bid lose their funds first.

- Members that lost the auction lose theirs next. Interesting that at LCH they seem to order these losses even further by your bid. So if you just nearly lost the auction, you are the last in this sequence. Also worth noting that with multiple portfolios (currency and sub-portfolios) this step is a bit complicated.

- Members that won the auction lose theirs last.

I find that interesting as you can see the incentives in place, and hence the importance of providing the best bid possible during an auction. And if not the best bid, at least having the technology in place to reliably calculate an appropriate bid in the appropriate timeframes so that you don’t end up first in line to contribute your default fund contributions!

A good time to remind everyone that a tool like CHARM does this reliably – more about this in Amir’s recent article.

5 – Unfunded Assessment

If the losses carry past the default fund, the clearing houses have arranged commitments for further funding. The rules here are a bit more sketchy, but generally seems that CME’s unfunded requirements are sized like the regular default fund, except that instead of the two largest losses, this is sized as the 3rd and 4th largest losses.

In LCH’s case, it would appear this number is quite larger – if I read it right this is equal to the funded portion of the default fund yet again.

6 – Last Steps

After all of the above, the LCH offer variation margin haircutting, where losses will be eaten away by taking portions of positive VM calls. LCH also have a concept of voluntary contributions. I can almost picture that meeting when firms are asked to keep going. Almost like a fraternity party gone wrong – I picture the frat house, burnt to the ground after years of parties, police and fire staff still there, and somewhere in what’s left of the foundation, a fraternity brother asks another “you want another beer?” I’d suspect the answer would be “Nah, I’m good, I’ll go home now”.

EDIT: It has been clarified that CME also has “gains haircutting”, with the haricut-ed amount being recoverable from the estate.

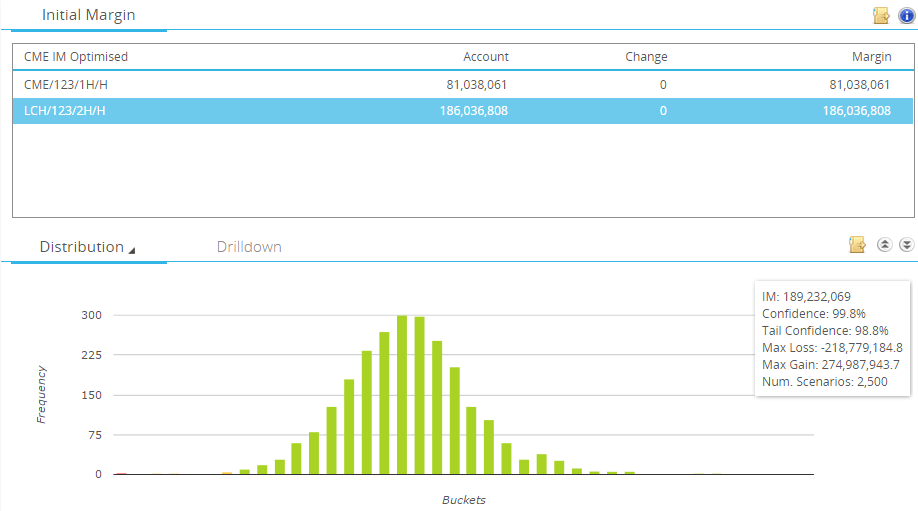

What is the Scale of All Of This

I found it hard to find real numbers on the default fund. But have put together the following based upon numbers found on the CME website and an RBA document assessing the default fund at LCH. All numbers in billions of USD:

The first two levels are specific to the defaulting member. Their initial margin is their own line of defense based on their portfolio, so could be anything – I’ve just labelled “X”.

The Clearing House contribution appears paltry when compared to the default fund.

The total default fund at each clearing house is over $3 billion.

What Did I Learn

I think there are a few takeaways from this.

First, changing the minimum default fund contribution from 50 million to 15 million would seem trivial, both to the clearing house as well as firms. I suppose there might be some new firms that would find this useful.

Most importantly, what I learned is the importance of providing a good bid during the auction. Without it, you move up the queue in offering your default funds to cover another members loss.