- Ring-fencing splits banks into deposit-taking institutions and investment banks.

- There is more than one way that this can be achieved.

- The European Commission has decided against ring-fencing.

- Large UK banks are required to ring-fence their deposit-taking operations from January 2019.

- The US may include some ring-fencing proposals as they look at financial reforms.

Why Do We Care?

Ring-fencing will split up any bank captured by the legislation into a “retail” arm and an “investment” arm. In terms of derivatives activity (i.e. what we tend to care about on this blog!) this may have the following impacts;

- Counterparty Relationships – will my trading entity change?

- Funding – what will it do to my cost of funding?

- Netting – will I need to bifurcate portfolios?

- Hedging – will the “retail” arm still be able to hedge a retail fixed rate mortgage with a swap? Will they automatically do this hedge with their investment arm? Just how “arms length” will these relationships be?

I’m not going to cover these aspects today as they are pretty broad-ranging, and would essentially just be my own personal opinion. But I think it is important that our readers take note that this is happening (in the UK) or not happening (in Europe) and be prepared for these changes to become part and parcel of market changes over the next year.

Why is Ring-Fencing even a thing?

The idea of ring-fencing can be boiled down as protecting deposits (both insured and uninsured) of end-users from the risk of “other activity” at a bank losing them all of their money.

A key idea is that investment banking activity incorporates:

- Leverage

- Financial innovations

When banks get carried away combining 1 and 2 (and let’s face it, financial engineering tends to be a way of getting more leverage into the system rather than removing it), there is a tacit recognition that financial regulation probably cannot keep up. This leads to the risk that financial institutions are under-capitalised and cannot survive a severe market shock (these do happen from time to time. Younger readers should be aware that BTFD has not always worked).

It seems unfair (particularly to politicians) that Fred Bloggs from number 54 should have his life savings put at risk by either rogue traders (Barings) or a reliance on market-based funding (Northern Rock, Bradford and Bingley…oh and Bear, Lehmans, Merrill).

The first step to protect Fred is to insure his deposit up to an attainable limit. This, in theory, makes a bank-run less likely. But it didn’t stop a run happening on Northern Rock in the UK. And it also relies on a sovereign nation to actually prepare for this insurance policy correctly, rather than just printing money to satisfy it, which (in times gone past) would lead to inflation and an immediate devaluing of the insured deposits.

The second step, once this insurance policy is in place, is to make sure that banks don’t get a free-ride from now-complacent deposit holders who consider the insurance policy a cast-iron guarantee. If the deposit threshold is set too high, and capital standards too lax, there is a moral risk that a bank could intentionally over-leverage themselves (via new, nefarious ways. Call it a “known unknown.”). Typically diligent deposit holders won’t blink an eye as the bank’s balance sheet becomes stretched because they trust their insurance policy. The bank might offer tantalisingly good savings rates (B&B, Northern Rock) and savvy depositors will fund the balance sheet up to, but never over, the insured deposit amount. But this removes a valuable market-based feedback mechanism. Over-stretched banks should find it more difficult to attract deposits and should have to offer much higher rates of interest to depositors. Otherwise, the taxpayer-funded insurance policy is subsidising the nefarious bank’s funding rate and hence is a direct value-transfer from taxpayer to shareholders (John Galt wouldn’t insure your deposits!).

The second step, once this insurance policy is in place, is to make sure that banks don’t get a free-ride from now-complacent deposit holders who consider the insurance policy a cast-iron guarantee. If the deposit threshold is set too high, and capital standards too lax, there is a moral risk that a bank could intentionally over-leverage themselves (via new, nefarious ways. Call it a “known unknown.”). Typically diligent deposit holders won’t blink an eye as the bank’s balance sheet becomes stretched because they trust their insurance policy. The bank might offer tantalisingly good savings rates (B&B, Northern Rock) and savvy depositors will fund the balance sheet up to, but never over, the insured deposit amount. But this removes a valuable market-based feedback mechanism. Over-stretched banks should find it more difficult to attract deposits and should have to offer much higher rates of interest to depositors. Otherwise, the taxpayer-funded insurance policy is subsidising the nefarious bank’s funding rate and hence is a direct value-transfer from taxpayer to shareholders (John Galt wouldn’t insure your deposits!).

Therefore, ring-fencing is a somewhat direct consequence of deposit insurance schemes. Think of it as a particularly stringent term of an insurance policy. And consider it almost impossible to compete in the market by offering uninsured deposits, just at a higher rate (maybe because no-one in the market is able to accurately price that “higher rate”….apart from Libor submitters).

So we end up splitting banks up. Leveraged, “investment banking” activity in one legal entity, insured deposits and “retail banking” in another legal entity.

In the US, these were the thoughts behind the Glass-Steagall act (and FDIC-insured deposits) as I understand them.

In the UK, we had a really low insured deposit amount until Northern Rock. So it wasn’t really an issue (until it was).

In Europe…..well, they introduced the whole EUR currency without any fiscal consolidation. That meant whole countries (Greece) were tempted to over-leverage due to the insurance (implicit) from insurance providers (Germany). Introducing a deposit insurance scheme across the whole of Europe was very much a second order risk compared to that….

What Is Happening in the UK?

For a great overview, I recommend heading over here. In summary;

UK banks are being ring-fenced, not being split up.

UK banks are being ring-fenced, not being split up.- As of January 2019, banks with over £25bn in deposits will have to be ring-fenced. This covers:

- Barclays

- HSBC

- Lloyds

- RBS

- Santander

- The Co-Operative

- The institutions will have a “structural separation” between the deposit-taking arm and the “risk-taking” arm. They will be allowed to share the servicing of both of these arms from the same entity.

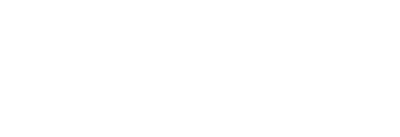

- If a bank has over £25bn in deposits in the UK, it will also have to hold a “Systematic Risk Buffer” of up to 3% of capital.

- All things combined, UK banks will now have to hold a minimum of 11% Tier 1 Capital.

Already, there are signs that UK banks are incorporating this extra capital charge (and maybe the anticipated higher funding costs) into investment decisions. For example, syndicated loans (a very balance sheet intensive business that normally sits within an “investment bank”) are being challenged.

And Europe?

Europe, just last month, decided to no longer pursue ring-fencing. There are several sceptics of ring fencing anyway (for example), but the timing seems strange. Would a European bank (via passporting) be able to take in £25bn of UK-originated deposits but not be ring-fenced? Is this a death-knell for passporting after Brexit?

Either way, it is not a great commercial development for UK banks on the international stage. Even if Santander and HSBC can somehow subsidise the cost of funding of their Investment Banks via international deposits, they still have to hold more capital in their UK businesses than a European bank.

Does the US want in?

There have been talks of reinstating a new version of Glass-Steagall in the US. This wasn’t mentioned in the recent Treasury review (or the Banking review as far as I can tell), but there certainly appears to be scope for discussion (a great overview here, and a proposed legislation from Senator Warren here).

There have been talks of reinstating a new version of Glass-Steagall in the US. This wasn’t mentioned in the recent Treasury review (or the Banking review as far as I can tell), but there certainly appears to be scope for discussion (a great overview here, and a proposed legislation from Senator Warren here).

In Summary

- Ring-fencing tends to be a consequence of deposit insurance schemes.

- The US had strict ring-fencing rules until the 1990s under “Glass-Steagall”.

- The UK is now putting into force ring-fencing rules that will affect the big six banks from January 2019.

- UK ring-fencing rules go hand-in-hand with more stringent capital requirements, but is less far-reaching than Glass-Steagall.

- Europe has decided to not pursue ring-fencing.

- It remains to be seen in the US whether financial reforms will include any aspects of ring-fencing.