I recently took a first look at Central Clearing of Bonds and Repos and in that blog I mentioned a Financial Statility Board (FSB) paper on Liquidity in Core Government Bond Markets. This paper analyses the liquidity, structure and resilience of government bond markets, with a focus on the events of March 2020; characterised as “a flight to quality, followed by a dash for cash”. In today’s blog, I will pick out what I found interesting.

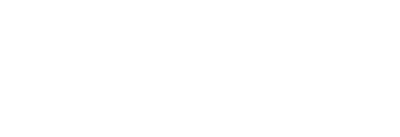

Stylised Lifecycle of a Government Bond

Let’s start with Figure 1 from the paper.

- Issuance by a Debt Management Office (DMO) to primary dealers

- Secondary trading of “on the run” bonds in the dealer market

- Use as collateral in repo markets, general or special

- Eligible for delivery in bond futures contracts

- “Off the run” bonds on the balance sheet of investors, held to maturity (HTM)

Showing the strong linkage between markets, primary to secondary and cash, repo and futures.

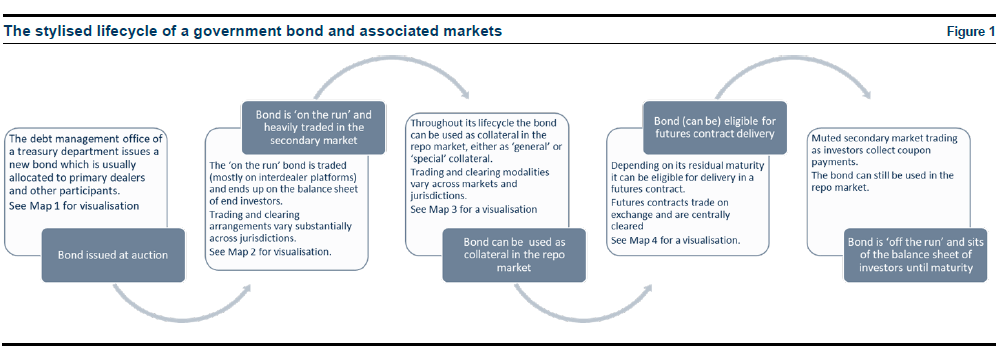

Debt Holders by Type

A graph on the holders of government bonds.

- Domestic Central Bank holdings increasing significantly in each country

- United States – Domestic non-banks the largest holders

- Germany – Others, followed by Domestic Central Bank

- France – Foreign non-banks, then Domestic non-banks

- United Kingdom – Domestic Central Bank (QE), then Domestic non-banks

- Japan – Domestic Central Bank (QE), then Domestic banks

- Italy – the most evenly split by type

There are also charts on the increase in size of Government Bonds markets, but not the clearest, so I will quote from the paragraph that introduces section 2.

- The size of core government debt increased substantially, both in absolute and relative terms.

- In the US, outstanding government debt grew from about $13.6 trillion in 2010 to $25 trillion in 2020 (or from 90% to 131% of GDP).

- In the euro area over the same period, government debt grew from €8.3tn to €12.9tn (87% to 113% of GDP)

- In the UK from £1.3tn to £2.9tn (80% to 137% of GDP)

- In Japan from ¥882tn to ¥1280tn (174% to 238% of GDP)

Puts some figures to what we all know; there is a lot more government debt to trade and hold.

The same section states that Government bond liquidity in normal market conditions has not deteriorated between 2011 and 2020, using data on bid-ask spreads, trading volumes and turnover ratios adjusted for domestic central bank holdings.

The paper goes onto cover March 2020.

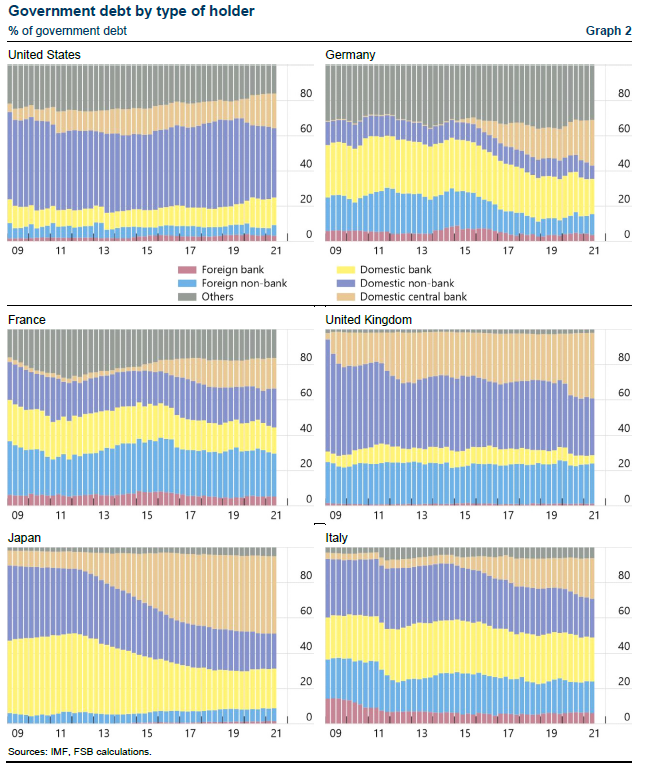

Market Dynamics in March 2020

The second paragraph from this section is re-produced below:

After providing more detail on Futures, Repo, FX Swap Basis and a comparison between jurisdictions, there follows a description of public intervention by central banks (re-formatted into bullet points and shown below):

- Such interventions involved significant asset purchases and liquidity support (e.g. reverse repo operations), which led to a US$7 trillion increase in G7 central bank assets in just eight months.

- Specifically in the US, the Federal Reserve alleviated strains in the offshore US dollar market by expanding FX swap lines and establishing a foreign central bank repo facility and in onshore markets by offering a significant amount of repo financing to primary dealers.

- In the euro area, the pandemic-related monetary policy measures included (i) the pandemic emergency (asset) purchase programme (PEPP); (ii) targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTRO III) at more favourable terms and conditions; (iii) non-targeted pandemic emergency longer-term refinancing operations (PELTROs); and (iv) easing of collateral rules.

- In some cases, these measures were also followed by targeted and temporary relaxation of prudential regulations (e.g. exempting banks’ government bond and central bank exposures from the leverage ratio requirements).

- DMOs also deployed various tools to address the turmoil in government bond markets.

- Feedback from stakeholder outreach confirms that central bank interventions were crucial to address the challenges in government bond market functioning during March 2020.

Behavior of Market Participants

Section 4 looks into the trading behavior of types of market participants in March 2020 and I would briefly summarise these five pages as:

- Dealers increased their trading activities across cash, repo and futures, did not add to selling pressure, but were not able to meet the higher liquidity demands and focused their market making on a sub-set of government securities.

- Principal Trading Firms (PTFs), while their is limited information, the evidence suggests PTFs did not suffciently increase their intermediation during the turmoil

- Hedge funds contributed to selling pressure in the US and some Euro area governments but were net buyers in the UK.

- Open-ended funds (OEFs) were net sellers of government bonds, their sales motivated by investor redemption requests, precautionary factors and re-balancing needs.

- Money-market funds (MMFs), Insurance Companies and Pension funds behavior differed across jurisdictions.

- Foreign entities, were net sellers of government bonds in all jurisdictions and especially the US, with the role of the US dollar as the global reserve currency the main explaination of larger sales of US treeasuries compared to other givernment bonds.

Drivers of Behavior

In section 5 the paper discusses and presents results of a survey the FSB conducted with relevant member authorities and Annex 4 has the findings from FSB outreach meetings. There is a lot to digest in these sections and not simple for me to do it justice; so I would highly recommend you take time to read it in the paper.

The point that interests me, was not the drivers on which there was broad agreement between dealer participants (un-certainity, one-sided flows, risk limits, operation issues, difficulty in hedging,.. ) but the drivers with the greatest discrepancy in responses:

Respondents also ranked factors that motivated the demand for liquidity, and those noted as “highly relevant” were

- MMF and OEFs needing to raise cash to meet investor redemptions

- Hedge Funds needing to unwind positions

Individual respondents also noted the following as highly relevant:

- margin calls faced by insurance companies and pension funds, who were ill-prepared for them

- portfolio relloactions by some investors that rotated from bonds into equities to take advantage of depressed valuations

- cash needs of non-financial firms (drawing down credit lines)

- foreign monetary authorities liquidated substantial amounts of US Treasuries

Policy Implications

Conclusions and Policy implications are discussed in Section 6 and here I will just present a few of the policy measures under consideration:

- mitigate unexpected and signifciant spikes in liquidity demand, which may involve selling (or repo) near cash-instruments such as government bonds

- enhance the resilience of liquidity supply in stress

- enhance markets’ oversight, risk monitoring and the preparedness of authorities and participants

For 2, the suggestion is for additional work on

- ways to increase availability and use of central clearing for government bonds and repos

- the use of all to all trading platforms

(The first bringing us back to my recent blog on Central Clearing of Bonds and Repos).

There is a lot more content in the FSB paper on Liquidity in Core Government Bond Markets.

To consider, digest and understand.

Hopefully the above has motivated you to give it a read.

We plan to cover more on this topic.